Years as JSU undergrad shaped philosophy, Judge Carlton Reeves says

By Jim Ewing

U.S. District Court Judge Carlton Reeves is an imposing figure on the bench at the federal courthouse in Jackson, but he breaks into a grin speaking of his years as a student at Jackson State University.

The 1986 grad says he almost didn’t go to JSU. “Thank God for OJ,” he said. Orange juice, that is.

In 1982, the Yazoo City High School senior had an Air Force ROTC scholarship at another university and was awaiting results of the required physical.

Meantime, he kept getting calls from Dr. Maria Harvey of the JSU honors program who thought he would be a perfect match. After months of waiting and time growing short before school would start, the physical results came back showing an anomaly. Apparently, although he had been told not to eat or drink anything prior to the physical, he had consumed some orange juice at a rest stop beforehand that threw off the results.

Since there was no time to retake the test, he called up Dr. Harvey and asked, “Is it too late to come to JSU?”

The rest, as they say, is history.

At JSU, Reeves, 51, met Lora McGee (class of ’86), the woman who would become his wife. Although they had both grown up in Yazoo City, he didn’t get to know her until he was in the last semester of his senior year. They were seated near each other in a business law class. He was smitten from the start.

Their daughter, Chanda, 20, is now a junior at JSU studying psychology.

LEGAL CAREER

Reeves’ legal career is quite distinguished. After graduating from the University of Virginia Law School in 1989, he worked as an extern with then-Hinds County Supervisor Bennie Thompson, now 2nd District U.S. congressman. He was a law clerk for former Mississippi Supreme Court Justice Reuben Anderson before joining the staff of the Phelps Dunbar law firm.

That led him to be tapped by U.S. Attorney Brad Pigott as chief of the civil division, from 1995 to 2001. After Pigott left the post, Reeves joined him as a partner in the firm of Pigott, Reeves, Johnson and Minor. In 2010, President Barack Obama appointed him to the federal court bench.

The prestigious list of jobs and people, Reeves said, all go back to the people, places and relationships he formed at JSU.

“I loved politics,” he recalls. He used to watch political conventions on television and was glued to the set during Watergate. He worked in Robert G. Clark’s failed 1982 congressional campaign. Naturally, he majored in political science at JSU.

“We had the most caring people at Jackson State in the Political Science Department” — Ally Mack, Les McLemore, Mary Coleman, Roy DeBerry, George Mitchell, Charles Holmes — “all of those folks had a genuine interest in our success.”

Holmes was the pre-law advisor “and he used to always encourage us to think about applying for law school and to think about going away because ‘you can always come back home,’ ” he said. “You can get into Ole Miss or Mississippi College but let’s just see if you can get to other places.’ ”

The outlook, said Reeves, encouraged him to apply to UVA. Holmes’ advice paid off for several of his cohorts, who went from JSU to law schools at Harvard, Yale, Stanford, Georgetown, Vanderbilt, and other big-name schools.

“And Jackson State prepared all of us to do that,” Reeves points out.

Rob Long, Lee Frison — “we all hung out together at Jackson State” — and another older JSU grad, Ottowa Carter, all went to UVA law school, he said.

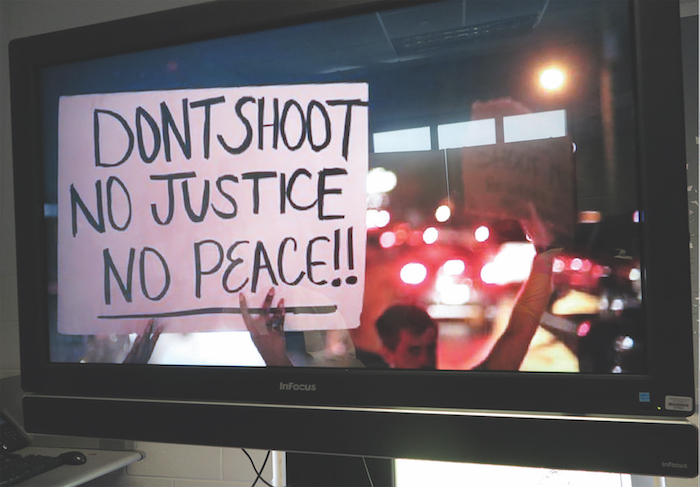

STUDENT ACTIVISM

Jackson State was a hotbed of activism when he was in school, Reeves said.

Protests were held against the Institutions of Higher Learning over funding. “We were always protesting, mostly led by a young man named Thomas Fox,” he said. “We marched on the state Capitol.” And they enlisted students from other Mississippi historically black colleges and universities to march.

The Jake Ayers college desegregation case was still only in its beginning stages.

While the federal lawsuit would eventually award $503 million to HBCUs in Mississippi for past underfunding, conditions were far different then. “At that time, the campus was small, the facilities were not up to par.”

At one protest, at Ole Miss, “I remember going up to one of the dorms and seeing just how nice their dorms were vis a vis what was at Jackson State. It opened my eyes.”

The Rev. Jesse Jackson came to campus in 1984 and led a march to the Hinds County Courthouse for JSU students to register to vote. It was at that march that Reeves got to know Lora better. They both marched and when it was over, the JSU cafeteria had already closed.

Lora was living with her sister who suggested he have dinner with them. “And we started dating,” he said. They married in 1990.

THE POWER OF A BOOK

Another experience at JSU, he said, that “opened my eyes” was a book. He thought he had a good education in Yazoo City, and he did, he said. But Professor Charles Holmes told him in his sophomore year that he should read the book Yazoo: Integration in a Deep Southern Town by Willie Morris.

Being from Yazoo City, he had met Morris and knew all the people mentioned in the book, but he had never read it. Morris’ wife, Jo Anne Pritchard Morris, had taught him in school.

His was the first class in Yazoo City that was integrated from first grade through high school graduation. They had the first integrated prom. But reading Morris’ book gave him a perspective that was at once encompassing, intimate and lasting.

Jackson State allowed him to grow as a person, he said.

As a member of the Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity, Reeves assumed some leadership positions. He also ran for Student Government Association president, but “I lost by just a handful of votes.”

Even that turned out well for him, proving a valuable lesson: A failure doesn’t mean you are going to fail.

The defeat, he said, changed his life, as he began to focus less on politics and more on becoming a lawyer. He took an internship at the Dockins and Wise law firm and that “gave me the opportunity to work in a law office and see what was going on and see how things are done, and it gave me a chance to meet black lawyers.”

Reeves struggled to find a way to get back to Mississippi, to find a job after he graduated from law school.

“I graduated in May and I had no money coming in.”

Working for Thompson helped him get the clerking job with Anderson that led to other opportunities.

“Again, relationships, people who care, who care about you, are fundamental.”

He said he has no ambitions beyond serving out his lifetime appointment of federal district court judge.

“I love this job,” he says. “I think this is the greatest job anybody can have.”

“You face all kinds of issues, and you are the judge. Unlike on the Court of Appeals or the Supreme Court, those judges have to get a second vote and, I guess on the Supreme Court side of things, it’s a miserable feeling I would imagine if you’re always on the 4 side of a 5-4 decision.”

VOTING MATTERS

Civil rights, police power and education are all issues that he faces, and they are all important, he said. They demand his attention, keep him up to date, and require great study. But to single out one issue that he finds important above all others, he said when asked, is to vote.

“But for the vote, I would not be where I am now.”

Also important, he said, is having African-Americans in the legal profession. Lawyers have always had privilege, always had power, he said, but in Mississippi most black lawyers are only first or second generation. Only a handful of blacks were practicing law in the 1960s in Mississippi. White lawyers can have generations of lawyers in their families, he said, and this has influenced law and public policy.

“In Mississippi, those who have been in power have been white people. You cannot disconnect the educational level, the economic status, and all that, the way the laws have been set up in the past, to prop them up on the backs of black folk. You cannot disconnect the condition of HBCUs and everything else, without tying it to that legal, historical context because Mississippi did everything legally to deprive people like myself of attaining that position.”

OPPORTUNITIES

Today, Reeves is a firm believer in JSU and HBCUs in general.

“I believe that those opportunities to allow me to grow came because of Jackson State — the things that we were involved in on campus and the people who cared enough about us to want us to succeed. I just don’t think those opportunities would come to individuals at the majority institutions. I’m a firm believer in the HBCUs and their nurturing.”

Jackson State University and HBCUs “give you the opportunity to learn about yourself,” he said. “I learned so much about Carlton Reeves, so much about Yazoo City, so much about Mississippi at JSU.”

In addition, he said, “you are encouraged, you are trained to do well, to be competent.”

If students aren’t tops in their class, a school like JSU “understands,” he said, with the approach that “you can give me something, and I can mold it. I can produce. Just give it to me. I can make it work. You don’t have to be the 4.0 students … we can make you productive citizens. All you have to do is want to learn. We can do that for you. I think HBCUs do that.” ONEJSU

High-profile cases

U.S. District Judge Carlton Reeves’ address to three young white men prior to sentencing in the 2011 slaying of James Craig Anderson, a black man, is now celebrated as one of the most powerful statements about racial violence in the South. You can read it at: http:// ow.ly/KyymT

In November 2014, Reeves granted a preliminary injunction blocking Mississippi’s ban against same-sex unions.

In his 72-page order, Reeves said, “Mississippi continues to change in ways its people could not anticipate even 10 years ago. Allowing same-sex couples to marry, however, presents no harm to anyone. At the very least, it has the potential to support families and provide stability for children.”

Leave a Reply