by Rachel James-Terry

Jackson State University’s political science department has received three grants, to date, totaling $410,000 from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to conduct innovative research that endeavors to understand the physiological ramifications of racially divisive subject matter on African-Americans.

Through a series of student and community participation studies, Jackson State political science professor Dr. Byron D’Andra Orey and his team examine the material health effects of exposure to police and protestor violence, Confederate imagery and implicit bias.

“It is an honor for me to be able to participate in such groundbreaking research,” said junior Jauan D. Knight. “Looking at the racial and political climate of our country, I believe it is past time for someone to find solid, scientific evidence of the effects of racism and these racially traumatic, stressful events.”

Orey, who is also principal investigator for the grants, explains that Dr. Evelyn Leggette, provost and senior vice president for Academic and Student Affairs, was decisive about students gaining opportunities to play major roles in the research.

Orey, who is also principal investigator for the grants, explains that Dr. Evelyn Leggette, provost and senior vice president for Academic and Student Affairs, was decisive about students gaining opportunities to play major roles in the research.

Under Leggette’s leadership, the Center for Undergraduate Research created a program to mentor undergraduate students. Orey said, “I applied and was awarded a small grant to mentor four students. Following this effort, I included funding for undergraduate students with the NSF grants. Over the three grants, roughly $75,000 has been appropriated for scholarships and travel.”

Topics addressing the Confederate flag and police force involving African-American males generate a range of emotions. But it was Orey’s rage, after leading and losing a referendum in 2001 to change the Mississippi state flag, that would prove to be a catalyst for the research his department is currently exploring.

“When we lost, we lost like 65-35. Folks didn’t want a change, so that was like a kick in the gut,” Orey said in his deep baritone voice.

“It had gotten to the point where that rage, the same stuff I’m studying, was affecting me. I thought I was going to lose it. I didn’t know what I was going to do – the flag disturbed me that much. The more I began to read about it, the more it actually increased my rage,” he exclaims.

Like many Mississippi youth, Orey grew up visiting the Vicksburg National Military Park. As a third-grader, he recalls wearing a Confederate hat to school and, after seeing a fellow classmate with a digital watch that played ‘Dixie’ – the de facto anthem of the Confederacy – he went home and asked his father to purchase him an identical watch.

“I couldn’t understand, at first, why he wouldn’t get me one,” Orey said, adding, “He did eventually get me a watch, but it didn’t play ‘Dixie.’ I now know why – the obvious story of it being rooted in slavery.”

The more Orey began to learn about the history of the Confederacy and its associated images, symbols and language the more he became cognizant of its prevalence throughout the South, which only intensified his anger.

Feeling disenchanted with his home state of Mississippi, Orey accepted an associate professor position at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln (UNL) and headed West.

Twin Data Studies

During his time at UNL, Orey discovered his colleagues were analyzing identical twins and non-identical twins to  determine if there was a genetic predisposition to people being liberal or conservative.

determine if there was a genetic predisposition to people being liberal or conservative.

“My position when we were doing the twin data stuff was that black folk have to have a certain type of gene to be able to survive and go through a traumatic experience similar to the post-traumatic slave syndrome (a theory sparked by researcher and social work educator Dr. Joy DeGruy Leary),” he said.

Orey also noticed a large number of studies administered by traditionally white institutions did not have many black participants; therefore “none of them was interested in any questions related to race.”

This prompted the professor, who has published a multitude of articles on race and politics, to ponder the effects of violent imagery on African Americans.

“This is just stuff you think about intuitively, but we wanted to see if, when you’re watching Facebook and a horrific shooting video pops up, like the Terence Crutcher video, the argument is people who see these videos can actually be doing physiological harm to themselves, and it’s unconscionable,” he said.

The idea of intersecting race, biology and political science stayed with Orey upon his return to Mississippi after accepting a chair position at JSU in 2008.

The Obama Effect

The first grant Orey received was for “Elite level queuing in the era of Obama.” The guise behind the experiment was to determine if the overwhelmingly African-American support of Obama translated into African-Americans supporting everything the president says and does.

“So, if Obama blamed blacks for their failures by suggesting that black males were simply not taking care of their responsibilities, this is why we have these inequalities, compared to Joe Biden, Colin Powell or Bill Clinton stating it. We wanted to see, essentially, and this is a crude analogy, if Obama said, ‘jump,’ do black people jump?’” Orey explains.

The results of the experiment showed, if African-Americans had a strong racial identity, they were more than likely to discount the president’s position if he blamed blacks for their failures as opposed to blaming the system. If the president blamed the system, blacks supported his position more than the position of other elites when they shared a similar perspective.

Race-based trauma study

The second grant Orey received from NSF was for the investigation of the biological effects that racially traumatic and stressful events and symbols have on African-Americans.

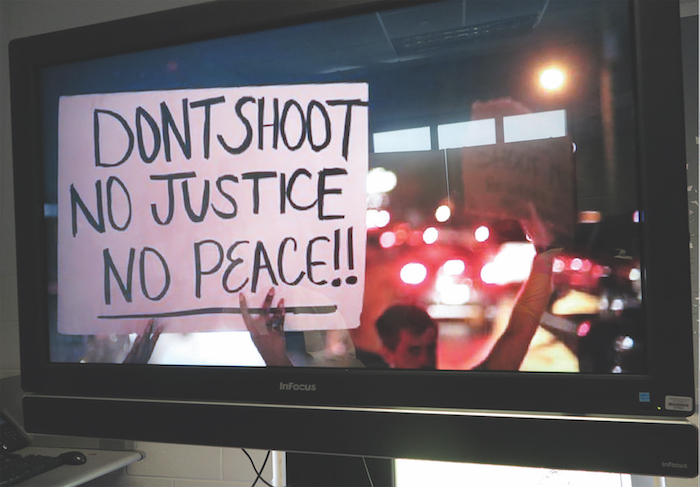

Participants are hooked up to a machine that monitors their sweat secretions (electrodermal), heart rate and facial expressions. They are then shown pleasant and startling images, at random, that include police brutality, protests in various stages of civil unrest, beautiful flowers and the Confederate flag among other things. So far, Orey and his students have only been able to test the electrodermal response.

“We have convenience samples right now of faculty, staff and students, but we will start paying people to take the experiments. In order to increase our data pool, we have to go beyond the university,” Orey said.

Active shooter simulator

The most recent grant from NSF will allow Orey and Dr. Yu Zhang, co-investigator and criminal justice professor, to analyze the impact of subconscious racial biases in the killings of black males using active shooter simulators.

The most recent grant from NSF will allow Orey and Dr. Yu Zhang, co-investigator and criminal justice professor, to analyze the impact of subconscious racial biases in the killings of black males using active shooter simulators.

First, one group of criminal justice students will undergo a week of cultural competency training designed to decrease the negative stereotypes associated with black people and strengthen racial identity. A second group of criminal justice students will forego the training.

Next, both groups will be given a subconscious test, based on a study out of Harvard, to detect if they are biased toward different ethnic groups and if the cultural competency training decreased any prejudice.

Lastly, students from both groups will wear state-of-the-art simulation goggles and be given an empty 9 mm Glock. The simulation goggles will project a variety of police-involved scenarios aimed at ultimately judging if they will shoot a black person faster than a white person. Their responses will then be correlated with their biases, if any.

“This is a pilot study, and we’ll observe if those that received the cultural competency training will see that black folks are not the negative stereotypes. Hopefully, any implicit bias will decrease. We then can put together a module to show that this type of training does reduce these types of shootings,” Orey stated.

One-of-a-kind research

Pointing out that JSU is conducting research similar to top universities like UNL, Harvard and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Orey said, “So we adopted similar methods and applied them to the unique experiences of African-Americans.”

Jasmine Jackson, a senior, agrees with Orey, “This research is significant because some may feel it does not fit into the field of political science or that the topics we study aren’t of any value to the field. But we are continuing to create a space for African-Americans in the area of political science,” she said.

Orey encourages and supports more student involvement in higher education research. “They have some of the most brilliant insight that has been untapped. These students know a lot more than what we think that they know,” he said, chuckling.

Knight appears to summarize the magnitude and overall aim of their research, stating: “It is not enough to just say, ‘I don’t like the flag’ or ‘I don’t like to see police killing black males,’ but it is another thing altogether to have solid physiological proof that people are traumatically affected by Confederate iconography and the police state. I believe the research we are conducting will have a lasting impact not only on my generation and race but also on our country as a whole.”

Congratulations Drs. Orey and Zhang for such ground-breaking research in this 21st century of violent numbness. The entertainment industries namely television, movies and music have seemed to capitalize on the subject of crime, violence and the criminal justice system. However, they have left out the most important element of what the impact of such so-called entertainment is doing to our young generations psyche and emotional well being. I watched yesterday as my 15 month old watched Chris Tucker and Jackie Chan fighting and karate kicking the so-called bad guys and was mesmerized and did not flinch. His parents did not notice that their young toddler was not afraid of the violent action portrayed on the television as they were engulfed in their cell phones and social media. But, I watched my grandson not move from the captivating stunts of kicking, socking and hitting with chairs and objects and he then began to take his teddy bear and hit his cousin who was much older. I cannot wait to see your results and recommendation at the completion of this study. Your findings, I know will be jaw-dropping.