[vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/1″][vc_column_text]

By RACHEL JAMES-TERRY

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/1″][vc_empty_space height=”32px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/1″][vc_column_text]

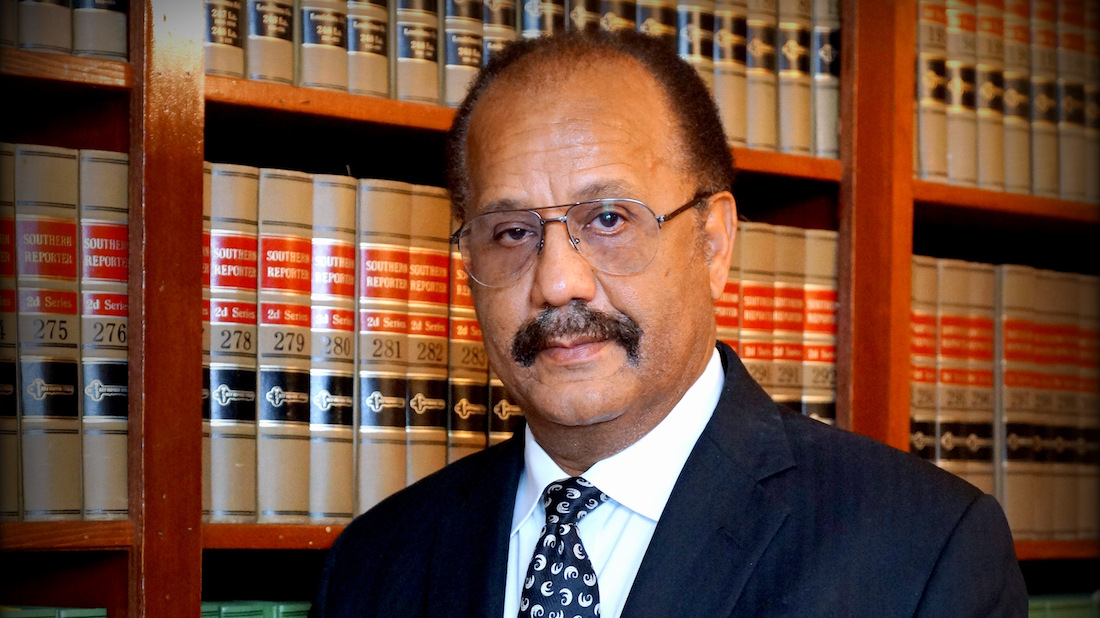

If one does not understand history, there is no understanding of the present and no vision for the future, said James “Lap” Baker.

It’s been nearly 50 years since Phillip Lafayette Gibbs, 21, a pre-law major at Jackson State College, and James Earl Green, 17, a student at the neighboring Jim Hill High School were killed by police on the campus of the HBCU on May 15, 1970. For Baker, it is an indelible day.

“It was a planned massacre in my opinion,” said the 67-year-old Picayune native.

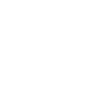

There does not appear to be any one thing that led police to the HBCU half a century ago. Some say it was protests while others maintain there were none. Rumors flew and books have been written that students or corner boys threw rocks at white motorists driving past Jackson State College that day. There were allegations students tried to burn down the ROTC building in opposition of the Vietnam War.

“There was no protesting going on. People who were not out there keep saying that,” Baker, a senior geography major at the time, said with some frustration. “They had a little march, I think, a day or two before that, but it had nothing to do with this. We were not protesting the Vietnam War. Trust me.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/1″][vc_empty_space height=”32px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/1″][vc_single_image image=”4448″ alignment=”center” border_color=”grey” img_link_large=”” img_link_target=”_self” img_size=”large”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/1″][vc_empty_space height=”32px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/1″][vc_column_text]

The repeat narrative among survivors is that students were simply fed up with bigotry and injustice. It was the end of the 1960’s, the same ‘60s in which civil rights leaders Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr. were assassinated. Pain had not dissipated for the black community and racial discord escalated, Baker implied.

“We had not forgotten where we were and who we were. They made a mistake,” Baker said of the police who converged on the campus that day. “They were dealing with the wrong students. We didn’t fear them or anyone else.”

Maybe it was the police who feared the students. After all this time, there is still no apparent justification for state police unleashing a torrent of bullets at unarmed students inside and outside the women’s dormitory, Alexander Hall. Baker and his roommate were returning from the store when they encountered officers.

“Late in the night, you hear and see white law enforcement officers marching,” he said pointing at a map of the campus that he brought with him. “They marched down from Prentiss to Lynch Street. They stopped at the first set of double doors (in front of Alexander).”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/1″][vc_empty_space height=”32px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/1″][vc_column_text]

Suddenly, a bottle was launched from the crowd of students standing in front of the dorm and it shattered on the concrete in front of the officers, according to Baker.

“When that bottle burst, all hell broke loose and over 400 rounds were shot. Not just on the Alexander Hall side but on both sides,” he shared. “James Green was not on the Alexander Hall side when he was killed. They shot in both directions. It didn’t matter to them.”

Baker and the other students hit the ground as fire flew over their heads. The senior clawed at the grass and crawled on his stomach before breaking into a run. “It was like we were in a military confrontation,” he exclaimed.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/1″][vc_empty_space height=”32px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/1″][vc_single_image image=”4452″ border_color=”grey” img_link_large=”” img_link_target=”_self” alignment=”center” img_size=”large”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/1″][vc_empty_space height=”32px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/1″][vc_column_text]

Baker said he didn’t stop running until he reached his apartment located behind the school. Seething with emotion, he picked up his .22 caliber gun with plans to head back to the melee. He admitted that it was a spontaneous reaction to seeing bodies scrambling for cover and hearing guttural sounds of fear and pain.

Once the barrage ended, Gibbs and Green lay dead and several other students wounded.

“I knew Phillip. I didn’t know James,” said Baker. “It got me when I found out he was killed. I couldn’t believe it. If you had known Phillip, he was a quiet person. He had a nice personality. He was not outspoken or boisterous.”

Hours after ceasefire, Baker and his friends returned to the campus where then-president Dr. John A. Peoples Jr. was able to restore some normalcy.

“He was the most together president I’ve ever seen. He stuck with the students. He never feared white folks or the system,” said Baker.

Peoples closed the school for the remainder of the semester. As a result, the class of 1970 was unable to have an official graduation ceremony. Instead, their degrees were mailed to them.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/1″][vc_empty_space height=”32px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/1″][vc_column_text]

In the fall, Baker caught a Greyhound bus to California. He had a scholarship to graduate school at San Jose State University and planned to major in geography. After seeing a land use map for the first time in an urban and regional planning class, Baker said: “This is what I need to take back to Mississippi for my people. I’m changing my major.”

In ’72, Baker became the first black student to receive a master’s degree in urban and regional planning from San Jose University. Similar to Jackson State College he had his degree mailed to him.

“My mother couldn’t afford to come. She made 78 cents an hour as a maid,” he explained. Even if his mother could attend, Baker still would have opted out of the ceremony. “I didn’t march. Blacks didn’t march. We could, but we didn’t want to. You would had to have been at San Jose to understand what was going on.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/1″][vc_empty_space height=”32px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”4456″ border_color=”grey” img_link_large=”” img_link_target=”_self” img_size=”large”][/vc_column][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

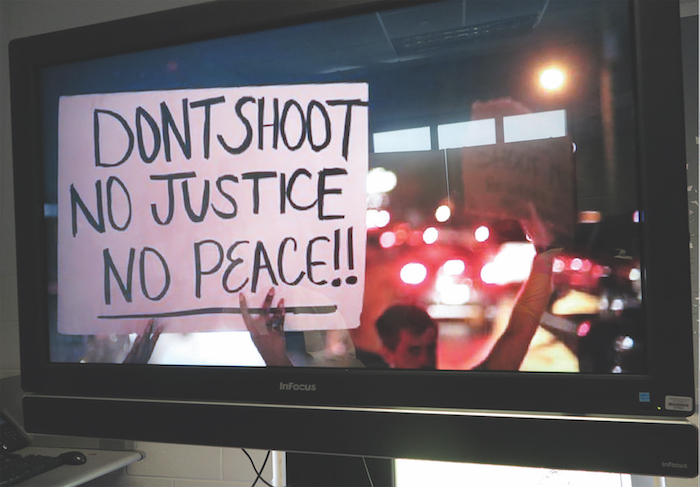

Later, Baker became San Jose’s first African- American city planner. He then worked briefly for the Santa Clara planning department. While there, he was vetted by the Louisville, Kentucky, planning commissioner.

“He told me, this is not a token position. You were highly recommended,” said Baker, who in ’74 became the first African-American city planner in the history of Louisville.

In 1977, he returned to Jackson, Mississippi, as director of planning and administration for the Mississippi Health Systems Agency. He became the first and only African-American to write the health plans for the state of Mississippi. He held the position for 10 years, before starting his own business, Comprehensive Planning Consultants.

For 24 years, Baker also taught urban affairs, geography and several other classes at JSU.

It’s rather easy to surmise that Baker never thought he would find himself being fired upon by police when he decided to attend Jackson State College. A high school honor student who excelled in sports and an all-state drummer, he planned to be a lawyer. But, life has a way of sending people on paths unforeseen.

For Baker, May 15, 1970, is forever imprinted on his brain.

“I can forgive, but I will never forget, not that night. Never forget where you come from. Know your history. History repeats itself, and you have to be prepared. You have to understand and recognize it when you see it.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Got a Questions?

Find us on Socials or Contact us and we’ll get back to you as soon as possible.