by Rachel James – Terry

A 10-year-old Augustine Emuwa is in another random Chicago city shelter. It’s number five or six of one too many he’s called home in his short life. The only other thing contending with his shelter record is the number of elementary schools he’s attended – eight – and he rattles their names off like items from a grocery list. Next to a newly made friend, he eats dinner while both their mothers hover nearby.

“So, I’m sitting here eating this food, and another boy that was pissed off that my buddy didn’t give him his cookie, walked over and hit him in the face with like a brass knuckle or something. He did it right in front of my mom, his mom and my buddy’s mom,” says Augustine, now 37.

The sheer viciousness of the incident shocked him into calmly getting up, walking over to a payphone and calling his father collect. When his dad answered the line, Augustine affectionately called Augie for short, told him: “Yeah, it’s time for you to take over full time. You got to let me come stay with you.”

Today Augie holds a bachelor’s in business from JSU, a master’s in education from Roosevelt University and is married with three young children but hails himself as the father of many. It’s a reference to his position as the principal of Chicago’s Gale Math & Science Academy. Rejecting limitations, he is also the brain behind Knits & Knots – a creative men’s brand that designs and produces unique and dapper neckwear for the classic man. Additionally, Knits & Knots sponsors the “Suiters Academy,” an eight-week fashion summer camp.

The camp offers 40 of the Windy City’s African-American male youth an apprenticeship-style learning experience. While the fashion component is the lure, kids gain the social and emotional learning skills they need to become entrepreneurs no matter their career path. At the end of the summer, the fashion students receive a $500 stipend to use toward start-up costs for a potential business. Augie’s story is an adversity-marred biography that ends with an awe-inducing triumph, that he attributes largely to his alma mater – Jackson State University. His father, a Nigerian immigrant, culturally believed babies and young children were to be raised by the mother. But doctors had diagnosed Augie’s mother with paranoid schizophrenia, which left little Augie spending the first six years of his life in foster care.

The camp offers 40 of the Windy City’s African-American male youth an apprenticeship-style learning experience. While the fashion component is the lure, kids gain the social and emotional learning skills they need to become entrepreneurs no matter their career path. At the end of the summer, the fashion students receive a $500 stipend to use toward start-up costs for a potential business. Augie’s story is an adversity-marred biography that ends with an awe-inducing triumph, that he attributes largely to his alma mater – Jackson State University. His father, a Nigerian immigrant, culturally believed babies and young children were to be raised by the mother. But doctors had diagnosed Augie’s mother with paranoid schizophrenia, which left little Augie spending the first six years of his life in foster care.

“When my mother got herself back together, she got me out of foster care. But, she would go off and on her medication, and that’s why, throughout my childhood, I ended up bouncing around from shelter to shelter to shelter. I can remember this stuff like it was yesterday,” he says.

Life with his “super rigid” West-African father provided Augie with a consistent form of structure and stability but “the nurturing and affection were super low, ” and expectations were extremely high. Among other things, his father’s Nigerian degree was rendered useless in the United States. Even after obtaining an accounting degree, the only steady work he could find was as a taxi driver. At age 15, Augie discovered his father inside their garage deceased from carbon monoxide poisoning.

“No one ever said suicide, but in my heart … I know my dad, and I remember him crying a lot. I remember him going through his own little personal thing,” Augie says in a faraway voice.

The former homeless kid took $5,000 he received after his dad’s passing and paid for a one-bedroom apartment for him and his mother on the far north side of Chicago. But Augie would occasionally come home to find his mother outside nude and talking incoherently due to bouts with her mental illness.

“It just wasn’t an environment where I could rest and get adequate sleep. I never told anyone,” he says. Instead, the teen persuaded his friends that life was good or so he thought, until they secretly followed him home from school to see his fabulous new digs.

“They saw my living situation and the type of building I stayed in, and one of my boys, Russell, told his mother, ‘Augie lives in something that looks like a crack house,’” he says, then laughs at the memory.

Eventually, Augie moved in with Russell’s family, and despite his grades bearing evidence of his personal burdens, he signed up for an ACT preparation class that helped him achieve a mid-20 score. The Chicagoan had never considered a school in the South until several friends piqued his interest to apply at JSU.

“A friend of mine was like, ‘You should apply to Jackson State because a buddy of mine is down there and it was a good fit for him. It’s smaller class sizes, that kind of thing.’ So, I was like; cool I’ll apply’.”

In 1998, Augie arrived at the HBCU with only $15 in his pocket, and the taxi cab ride from the train station cost him half of it.

“When I got accepted into Jackson State, it was my ticket out. That place completely changed my life, and that’s why I’m such an advocate for J-State.”

While a co-principal at Chicago’s Sullivan High School, Augie promoted Jackson State to his students. Many took his advice, including Sullivan’s valedictorian Ornella Amoah who is currently a junior at the university. “Her entire family is from Ghana by way of Italy. I drove them all down to Jackson State to get her enrolled,” he says proudly. The principal position at Gale Math & Science Academy was offered to Augie due to him and his co-principal significantly improving statistics at Sullivan – once considered one of the lowest-ranking schools in its district. Under their leadership, suspensions were reduced by 86 percent; freshmen enrollment increased by 60 percent; attendance increased by 7 percent and the graduation rate improved by 20 percent. He credits two JSU professors for his hands-on paternal approach to education.

“Dr. Princess Jones. Unfortunately, she passed a few years back, but she was my English professor. She was always so warm but stern at the same time, and I couldn’t understand for the life of me why this woman took a personal interest in me,” he says.

Laughter is interwoven in his recollection of Jones calling his dorm room demanding that he “get up and submit another draft – and another draft – and another draft.”

He added, “That woman was a huge blessing to me. She really fine-tuned my writing. I had never just seen anybody reach out to kids like that during their off time.”

He added, “That woman was a huge blessing to me. She really fine-tuned my writing. I had never just seen anybody reach out to kids like that during their off time.”

Not only did his writing improve, but so did his sense of fashion – going from baggy jeans to tailored slacks, partly due to his marketing professor, Dr. J.R. Smith.

“He used to pick with me a lot and tell me: ‘I can’t stand when you come in here with that slouchy style. You’re the last one that needs to be wearing dirty denim,’” recalls Augie before chuckling. “That very personal dad kind of touch was how he treated me as my professor, and I just remember carrying that with me. It’s the same way I talk to my students now.”

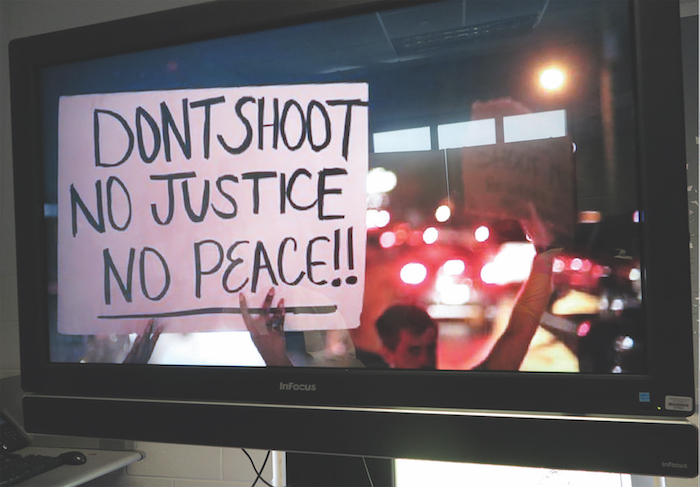

Transformative is one word the alumnus would use to characterize his experience at Jackson State. He makes it clear that the university helped to cultivate his self-esteem and pride. The principal says, that for an African-American teenager from a “jacked up situation” who had run-ins with the police, JSU furnished an opportunity for him to see “professional, authentic black people,” he says.

“I got a chance to see black people in a way I never got to see in Chicago. I’m not saying they were not in Chicago. I love Chicago. We have great folks in Chicago; that just wasn’t my life. So, when I got to Jackson State, it was an incubator that was feeding me positive images of people who looked like me.”

After a cerebral pause, Augie says, “They almost reconstruct you a little bit from the inside out. That’s what I’m trying to do in education. I want to build the interior and the exterior, so we can have a product that’s really polished, and that’s what Jackson State did for me.”

Amazing story! So proud of you!

Im proud of you for allowing your situation when you were young to cause you to be motivated to do more. Didn’t allow your poor situation to destroy you but allowed it to become a reason to excel for the best.

Im proud of you for allowing your situation when you were young to cause you to be motivated to do more. Didn’t allow your poor situation to destroy you but allowed it to become a reason to excel for the best.

Amazing story! So proud of you!

Absolutely wonderful! What an inspiring message. Keep up the good work and if you’re ever down south again, I would love for my neighborhood kids to hear your story.

Augie you are an amazing human being. Bless you for guiding others on to a great and positive path. I hope your Mom has found the healing needed for her illness. You Rock! ?

Awesome testimony!