[vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/1″][vc_column_text]

By L.A. WARREN

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/1″][vc_empty_space height=”32px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/1″][vc_column_text]

“Why did you shoot them?” asked Gregory Antoine, a student at Jackson State College in 1970 who witnessed, immediately approached and questioned local and state police after they unleashed a hail of gunfire that killed two unarmed students and injured a dozen others.

Dr. Antoine, a 1972 graduate of Jackson State and native of Pass Christian, Mississippi, is now a physician who has saved many lives, including victims who lost legs during the deadly Boston Marathon Bombing in April 2013. Then, he was chief of plastic surgery at Boston University School of Medicine. At Walter Reed Army Medical Center, the retired colonel and veteran of the Army and Navy had operated on military rangers who had been ambushed by Somalis when a Black Hawk helicopter was shot down in 1993.

Although not a physician in 1970, he rushed to aid mortally wounded Phillip Lafayette Gibbs, 21, a JSU pre-law major. “It was a futile effort,” said Antoine, associate dean of Clinical Affairs and chief medical officer at Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta.

“He was wheezing. Now that I’m older I realize he suffered a sucking chest wound,” said Antoine, who recalled being partially covered with Gibbs’ blood. “He was trying to breathe, making noises. I assumed he was shot in the chest. I kneeled beside him, touched him, turned him. He was still alive at that time, but I believed he died right there.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/1″][vc_empty_space height=”32px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

The 29.2-second firepower also snuffed out the life of James Earl Green, 17, a student from Jim Hill High School in the Jackson Public School District. Meanwhile, other victims were wounded by bullet fragments and broken glass or trampled during a stampede by startled students.

Antoine recalled other details of the early-morning horror of May 15, 1970, that is now immortalized and observed annually as the Gibbs- Green tragedy. Shortly after midnight he watched as police “raised their weapons simultaneously and opened up with a barrage of fire. Suddenly, the night sky lit up,” Antoine said.

However, just a day before, he said he saw no signs that earlier protests would devolve into mayhem and “murder” – the latter of which is a description by some observers of the tense, deadly situation.

“There was a group protesting about Cambodia. It was a small demonstration about the invasion. They were just regular students, protesting and chanting. They were protesting that (President Richard) Nixon had invaded Cambodia and believed that was an expansion of the Vietnam War,” Antoine said.

“During the day, there had been some issues with Lynch Street. There was a lot of traffic in the middle of campus, including rock-throwing at white people riding through campus. Of course, there were complaints to police about that.” He also remembers a fire near Robinson and Lynch streets that further fueled tensions.

Moreover, Antoine downplays the role of corner boys. Many people have blamed them for much of the disorder and attacks on white motorists, who were accused of taunting JSC students.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/1″][vc_empty_space height=”32px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/1″][vc_column_text]

“I don’t think corner boys were the prime conspirators. We had pretty much gotten the corner boys under control by 1970. Yes, there were still some instances of them causing trouble. In fact, I hung out with a group of guys, and we befriended some of the corner boys and even got into fights with them. We said, ‘You may be corner boys, but we are not afraid of you. We must learn to peacefully co-exist.”

On the night leading to the onslaught, Antoine said he had been studying in the Just Science Hall when he heard a commotion outside. He ventured outside and ran into then-Dean of Students Tommie Smith. They walked toward a men’s dormitory and saw a cadre of police officers entering the campus. He said as police stopped in front of the dormitory, students began tossing items from windows at law enforcement.

“I overheard one say, ‘If they continue to throw stuff, shoot up there at them,’ ” recalled Antoine, who walked toward the windows to urge his fellow students to stop.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/1″][vc_empty_space height=”32px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/2″][vc_empty_space height=”32px”][vc_column_text]

Soon thereafter, Antoine said police marched farther onto the campus as he and the dean walked on the opposite side of the street. “We moved onto the grassy part, and we watched the cops position themselves in front of the dormitory (Alexander Hall). Students were still there camping. They were not doing anything other than chanting, ‘Hell no, we won’t go.’ Many people didn’t want to get drafted to go to war.”

Moments later, the shooting began. Antoine said it lasted for many seconds. That’s when he quickly noticed Gibbs. He said he asked one of the leaders of the Mississippi Highway Safety Patrol, Trooper Lloyd Silas Jones, to call an ambulance. Antoine said he heard Jones tell emergency dispatch “we have niggers down.”

As an eyewitness to those events, Antoine eventually would testify at Congressional hearings about the incident. In D.C., he met with Nixon’s domestic adviser. Beyond this, he and others had formed a committee of concerned students and had worked side by side by a person identified as “our voice,” activist Constance Slaughter. At the time, Slaughter was the student body president at Tougaloo College and had led protests against injustices. Today, she’s a renowned lawyer.

Their student panel also raised a few hundred dollars for Gibbs. They drove to Ripley, Mississippi, to present the gift to his family.

As for the rest of that fateful night, Antoine said the high-intensity episode “is now sort of a blur – maybe due to PTSD.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/1″][vc_empty_space height=”32px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”” top_margin=”none”][vc_column type=”” top_margin=”none” width=”1/1″][vc_column_text]

Looking back, he said he doesn’t think there was anything else students could have done to avert the nightmare because of the “overwhelming firepower” of law enforcement.

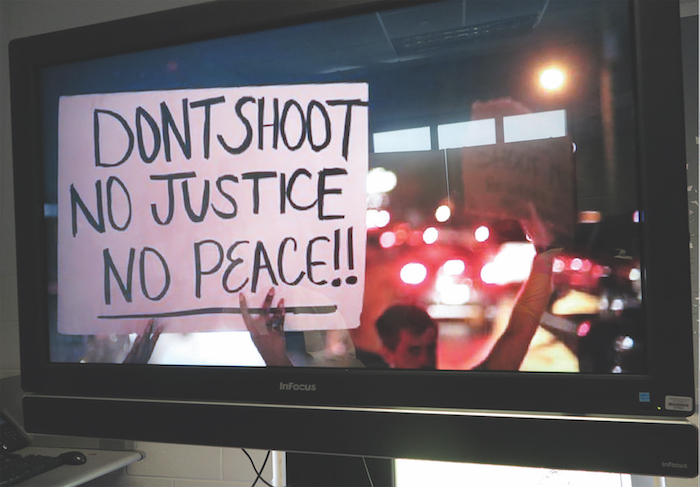

Sadly, he said, “The 1970 tragedy was a waste of two African Americans’ lives and a precursor to how young African American males are being treated right now. Apparently, we are expendable.”

Antoine said the Gibbs-Green tragedy should be remembered as a reflection of the atmosphere of the current government “that is really not for everybody because the Constitution can be twisted to fit whoever is in power.” He also blasts gerrymandering, disenfranchisement and racial-profiling.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Got a Questions?

Find us on Socials or Contact us and we’ll get back to you as soon as possible.