By L.A. Warren

Jackson State University student Anissa Hidouk says she experiences “reverse culture shock” when visiting her Algerian homeland, a nation that voted in March to criminalize violence against women who are often abused.

“Women have to watch their backs and choose where they hang out because we have a lot of sexual harassment in the streets.” However, she still has an affinity to Algiers, the capital and her birthplace, because her family resides there.

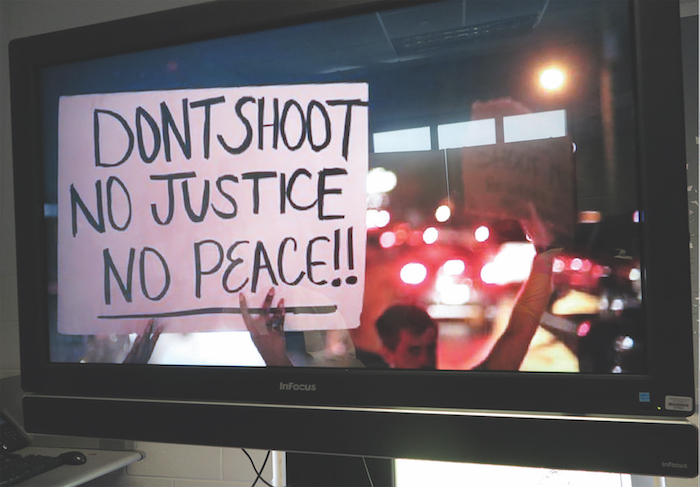

Hidouk said her mother was anxious about her move to the U.S. because she had heard of many shootings, but Hidouk calls the U.S. a land of opportunity. “Personally, I feel more threatened back home than in the U.S.,” said Hidouk, who speaks highly of its economic, political and social advantages.

Still, she said, “it’s scary to be in a country where you don’t know all the laws, and if I lose my passport I’m basically nobody.”

In a culture where families try to protect females, relatives were against her plans to study abroad.

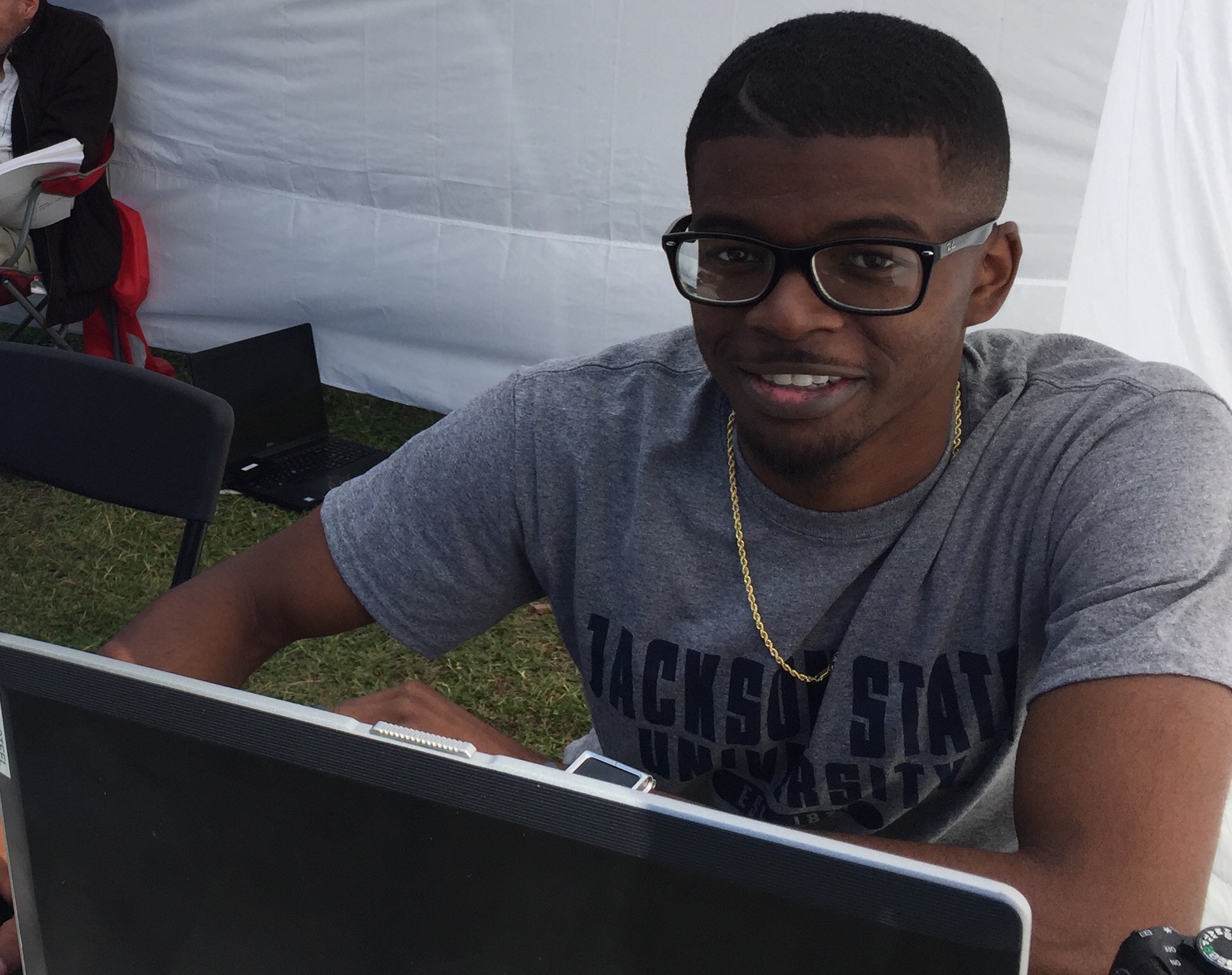

However, Hidouk credits her father for spearheading her departure to JSU. Although Hidouk lacked solid English-speaking skills, her eldest sister, who earned an MBA at JSU, urged her to enroll in 2011 with another older sister.

She spent two months of intensive study in the English as a Second Language program. Because of the language barrier, the first semester was tough, but “my professor and the faculty were really helpful.” She’s now a junior pursuing a degree in marketing.

As a Muslim, it took her time to adjust to cultural differences such as religion and food. Nevertheless, Hidouk said living in the U.S. remains the best decision.

“Generally, I can do whatever I want here. Because I’m free only when I get married in Algeria, my parents wanted me to have an international experience to help me grow.”

She said U.S. parents don’t mind children dating, but, in Algeria, “a woman has to stay pure until marriage.”

Furthermore, Hidouk said males or females don’t live by themselves even if they’re 30 or 40 and that, due to expenses, some married couples live with their parents.

I want here. Because I’m free

only when I get married in

Algeria, my parents wanted

me to have an international

experience to help me grow.”

“Because we don’t learn to be totally responsible in Algeria, I’m glad my parents allowed me to face difficulties on my own here.”

She said she doesn’t understand why many struggling U.S. adult offspring never return home.

It seems, she said, that some parents don’t necessarily feel obligated to care for older children. “In Algeria, our parents make us rely on them.”

Even though Hidouk appreciates the friendships, freedom and prosperity in the U.S., she suspects her attachment to family and culture will lure her back to “conservative” Algeria.

The decision will be difficult, however, since in the U.S., “anyone can start out poor and become a millionaire.”

Compared to her friends in large northern U.S. cities, she said her adaptation to American culture is easier in a smaller place such as Jackson.

Also, she said she’s impressed with the size of the international community on JSU’s campus. Describing Algeria as rude, she said Mississippians are refreshingly hospitable.

“They greet you, open doors for you and never make fun of your accent,” she said, adding, “JSU has changed my life forever.” ONEJSU

Leave a Reply